"PETERLOO" - It’s a word we’ll be hearing a lot of in the coming months - as we approach the bi-centenary of a massacre of protesters in Manchester, England.

Descendants of Mancunians everywhere - and there will be a good many in Clay County - will commemorate the tragic episode which occurred in their home town, on 16 August, 1819.

When unarmed and entirely peaceful men and women attended a demonstration in favour of voting rights they were attacked by the military. At least 15 people were killed (including four women) with more than 600 injured - slashed by sabres or crushed by horses. It is hard not to see the tragedy in parallel with that which occurred 190 years later in Tiananmen Square, China, and it was an iconic episode in English history.

Poverty and oppression drove Mancunians to flee their native town; many emigrated to America, and some settled in towns such as Manchester, Kentucky. The culture these immigrants brought to the new world still survives. They brought their folk music to many a sleepy hollow in Appalachia and introduced clog-dancing (‘clogging’) which became Kentucky’s official state dance. As Kentuckians know, there is nothing quite like the sound of the foot-stomping rhythm that can be made by clogs - sturdy leather footwear with wooden soles, sometimes fitted with iron caps on heel and toe - when cloggers dance to the accompaniment of enthusiastic fiddle-music. The tradition has danced down through the centuries on both sides of the Atlantic and is a vibrant reminder of something else our two towns have in common - the love of democracy and freedom of expression.

The American War of Independence which set England’s Thirteen Colonies free from autocratic rule, was an inspiration to the poverty-stricken cotton workers in Manchester, England, as was the French Revolution. Voteless and voiceless, however, they sought to bring about democracy by peaceful means. As powerless workers in new mills and factories they were children of the Industrial Revolution, and wanted to change society to take account of the rapid growth of industrial towns.

So it came about on that fateful day in 1819, that shortly after two o’clock under a cloudless sky, troopers of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, their work done, dismounted, in order to ease their horses’ girths, to adjust their accoutrements, and to wipe the blood from their sabres.

The venue was an open space known as St Peter’s Field, and in a parody of Wellington’s famous victory over Napoleon at Waterloo, a few years earlier, the event became known as Peterloo. This master-stroke of journalism from the pen of an impoverished Manchester bookseller named James Wroe eventually ensured publicity for the wrongs done on that day; a seminal moment in the history of democracy.

Manchester men like Wroe, and brave Radical colleagues such as Elijah Dixon and Joseph Johnson, suffered arrest and imprisonment without trial for daring to challenge the established order. Often, their families were persecuted, their homes broken up while in prison, and their wives and children thrown into the workhouse.

Some years later, Manchester men were at the forefront of the campaign to save six agricultural workers from Dorset from being transported to a penal colony in Australia for daring to organise a trade union. We know they were not successful, and the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs showed just what a long, hard road would have to be travelled before ordinary men and women could win democratic rights.

Over the years these events were largely forgotten, but the bi-centenary has provided a major boost to the campaign for a memorial to the victims of Peterloo, close to the site of the massacre. So will the soon-to-be-released film ‘Peterloo’, directed by Oscar nominee, Mike Leigh.

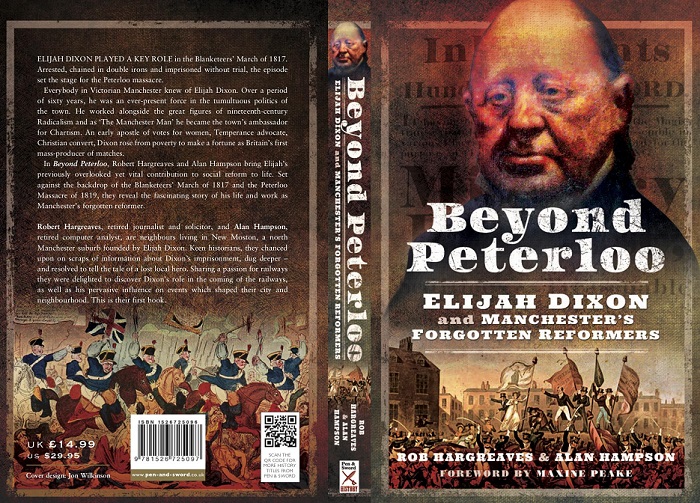

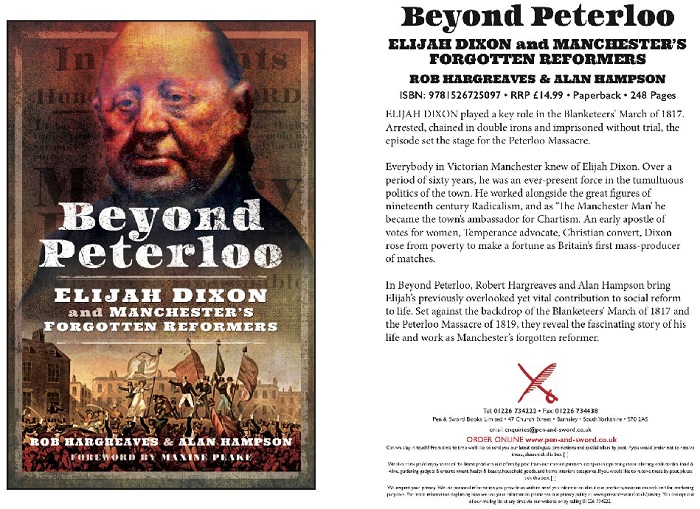

Star of the film, Maxine Peake, has written a Foreword for a new book on the subject, written by Manchester neighbours, Alan Hampson and Rob Hargreaves**, which traces the slow progress of the English reform movement, and stresses the importance of an earlier event, the Blanketeers’ Match of 1817, which was also broken up by soldiers. Its leaders were arrested, clapped in double irons, and transported to London at night, interrogated by the Home Secretary, and imprisoned without trial.

In the nineteenth century, Manchester, England, at the heart of Lancaster County’s cotton industry, was inextricably linked to America through the import of raw cotton produced in the Southern slave-owning states. Kentuckians mainly supported the Union side in the Civil War which led to the abolition of slavery - but just as in Manchester, England, there were some in Clay County whose sympathies lay with the South. Buttons for Confederate uniforms were made in Manchester, England, and some mill-owners financed attempts to break the Union blockade of the South. But the loudest voice of the Lancashire cotton workers was heard in favour of abolishing slavery - even though it meant being put out of work, and near-starvation. At the height of the Civil War President Abraham Lincoln paid tribute to their sacrifices during the ‘Cotton Famine’, and when he was assassinated Elijah Dixon ensured that a message of condolence reached his widow on behalf of the workers of Manchester. A statue of the President now stands in Lincoln Square in the centre of Manchester.

Elijah Dixon was motivated by strong Christian beliefs, and by an innate knowledge of the lasting truth that all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.

** 'Beyond Peterloo', Elijah Dixon and Manchester’s Forgotten Reformers’ by Rob Hargreaves and Alan Hampson,

published by Pen and Sword, UK £14.99/ US $29.95

The attached images show the book cover, a typical Manchester cotton mill in more peaceful times, and the authors at the recent launch at Waterstones book store.